Originally posted in the American Farm Bureau Federation’s Market Intel Report

Inflation is usually caused when too much money is put into circulation by a central bank (like our Federal Reserve Bank) to pay for government debt or just to stimulate economic activity. This can overheat an otherwise well-balanced economy.

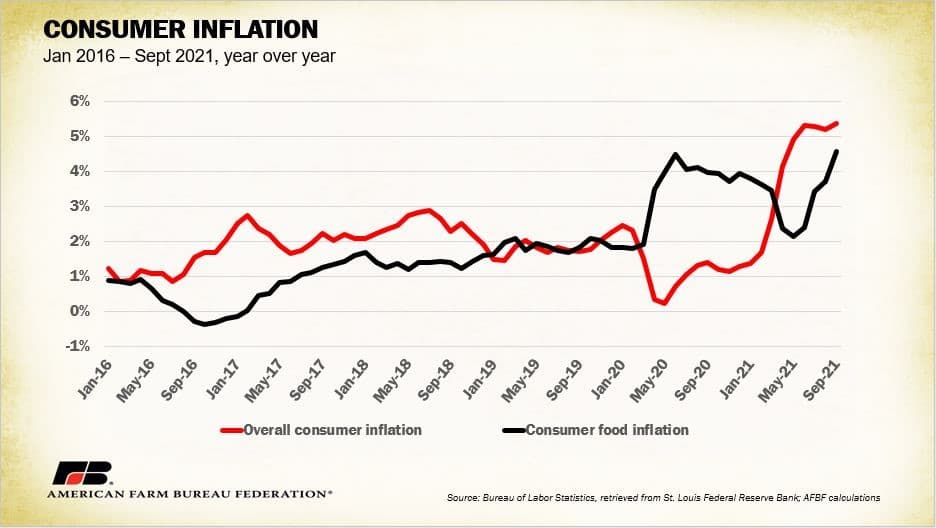

Today we face a different sort of inflation (September’s consumer price index was up 5.4% from last year), with specific disruptions cascading throughout the economy, leading to general shortages and price increases. This is similar in many ways to inflation during wartime, when governments take dramatic economy-distorting steps to deal with the crisis, the shape of demand changes suddenly, and certain production and trade flows are interrupted.

Government Action and the Economy

In most countries, government responded to the pandemic by mandating or encouraging the closing of offices, stores and other places of business. Even after reopening, public health rules and guidelines have encouraged many to stay home for work and leisure.

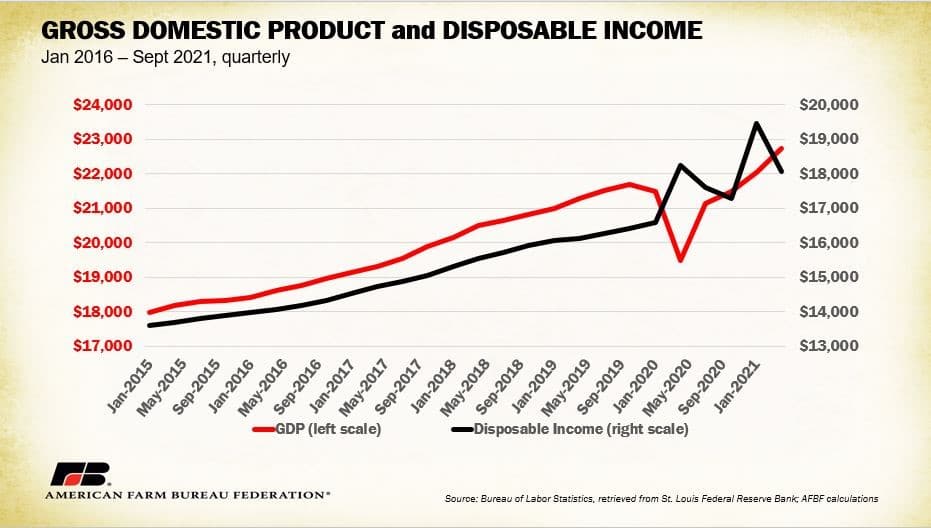

Massive government spending in many countries, including the U.S., provided continued spending power for many of those put out of work; this kept overall demand for goods and services up, even as their production was slowed by the lockdown.

Finally, anticipated rules mandating that companies with over 100 employees require vaccination or testing will have some impact on labor availability in an already tight labor market. More immediately, announced policies requiring federal employees to receive their vaccination by Nov. 8 as a condition of employment could leave USDA and other agencies short of the graders, inspectors and other staff required to keep food and other products moving through the market.

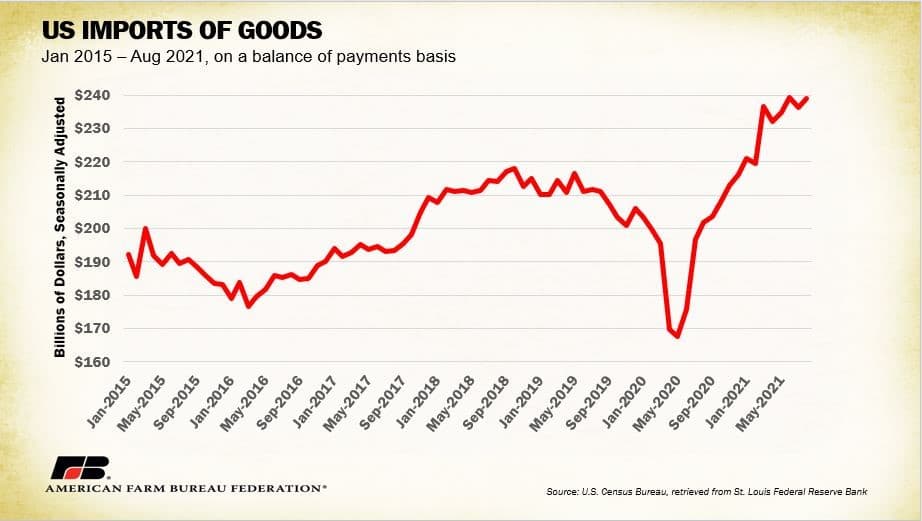

Demand

Lockdowns around the world in 2020 caused many people to shift their spending from services to goods. In the food business, this meant fewer meals away from home and more meals at home. For many people, it also meant spending less on outside entertainment (ballgames, shows, concerts) and spending more on stuff (electronics, furniture, kitchenware, home exercise equipment), much of it bought online and much of it imported. This left brick-and-mortar restaurants, stores and venues empty, even as it strained the ability of the world economy to make and ship the stuff people were buying online.

Breakdown of “Just In Time”

The red-hot economy of 2019 was a finely tuned machine. Manufacturers, farmers, restaurants and retailers relied on what they needed to be delivered “just in time.” They got just what they needed, just when they needed it; this kept down their inventory costs and made the economic machine as efficient as possible.

The lockdown economy of 2020 began with consumers panic-buying milk, toilet paper and other staples. The demand shifts discussed above created imbalances in the economy, leaving businesses with the wrong mix of inventory to meet the new demands. The fine-tuned machine was tilting.

There weren’t enough container ships or container port capacity to move everything we wanted from Asia. As of this writing, 77 container ships were waiting at anchor for a berth to unload at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach; this number is normally zero. Rail freight was short and getting more expensive. There weren’t enough computer chip factories to supply the electronic brains of everything from computers to cars. To add to the difficulties, a Texas ice storm and power failure in February, along with Hurricane Ida in August, crippled parts of the nation’s petroleum/natural gas/plastics industry, leaving the country short of many key industrial ingredients.

The same logistics experts that had pushed “just-in-time” inventory management began telling the world’s producers instead that they should stock up “just-in-case”; that they should be more resilient. This business version of over-buying milk and toilet paper has become sound advice for individual companies this year, but it has had a similar effect as the panic-buying at the grocer: some things became expensive or hard to find.

And, yet, there is not a great rush to make the investments in new capacity for some of these bottleneck products and services. Some of these businesses are profiting from high prices for their short supply. Some may see their customers’ “just in case” over-ordering as part of a normal inventory cycle, in which orders will taper off once their customers are comfortable with the size of their stocks. Why build more capacity if this is a temporary rush? What makes this unusual is that the new uncertainty in the supply chain has reset every industry’s inventory cycle at the same time, with implications for the overall economy.

How It All Comes Together

Pandemic inflation, then, isn’t about too much money chasing the same amount of goods. It is about COVID’s reshaping of the details of supply and demand, the selected shortages coming out of those changes, and those shortages having cascading impacts through the many supply chains that make up our productive economy.

The COVID pandemic presented us with price increases across the economy because COVID has tilted the finely balanced economy of 2019 into the lockdown economy of 2020 and the chaotic recovery of 2021. It will take time and investment (and labor, a story for another day) to build out the capacity to fine tune our supply chains again. In the meantime, we may have to wait for that new truck and pay more for it when gets here.

###

Roger Cryan – American Farm Bureau Chief Economist